Personalisation and lifetime value

What is Customer Lifetime Value?

One might have heard that it is important to calculate and track Customer Lifetime Value (CLV). What is more interesting is that during our projects with clients, we have observed every single business having a slightly different definition of what they consider to be CLV and how they calculate it.

The most simple and straightforward definition of CLV could be:

“Customer lifetime value is a concept which estimates how much money the customer is going to bring to a company in the long run.”

However, this definition is quite broad and does not explain how to calculate it and what it is really used for. In this article you will find out:

- What is CLV and how to calculate it

- What are the main use cases

It is not enough just to know the areas where CLV can be used to improve business as described previously. It is also important to choose the right way to calculate CLV; the most suitable method depends on several factors:

- How mature is the business?

- What is the role of CLV, and how will it be used?

- What kind of data is available?

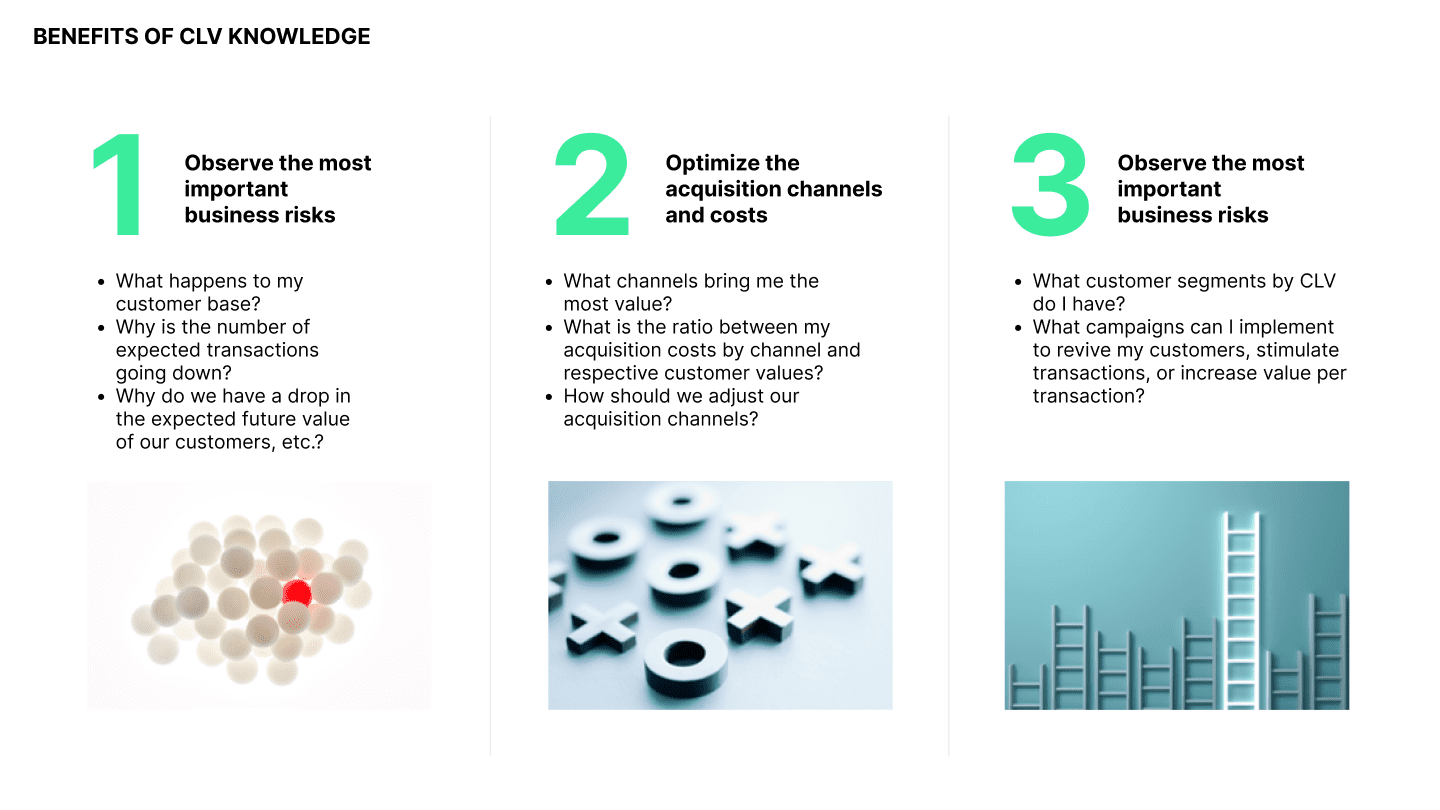

First, which are the benefits of tracking CLV? At CIVITTA, we see three main areas where CLV is important:

- Observing the business – CLV is used as one of the KPIs that provide information about the health of the business and customer base. CLV allows understanding how strong the current customer base is and track how it is changing over time, as well as identify reasons why it is changing (e.g. CLV is decreasing, is it due to average spend per customer decreasing or are customers churning more?)

- Optimize acquisition – the concept of CLV especially when used together with marketing attribution modelling — to come up with correct customer acquisition costs information — is a strong tool which allows to identify and target user groups which are expected to bring the most value, as well as understand if these customers are generating positive return on investment. This allows to better understand marketing costs in various channels and campaigns, and differences between multiple customer segments.

- Increase value of existing customers – if sophisticated enough methods allowing to calculate CLV for individual customers are used, the business is enabled to use CLV as a operational tool allowing to early identify the risky customer segments and act accordingly (e.g. run a specific campaign for customers who have high likelihood of stopping using the service).

Different ways to calculate

CLV based on company maturity

It is not enough just to know the areas where CLV can be used to improve business as described previously. It is also important to choose the right way to calculate CLV; the most suitable method depends on several factors:

- How mature is the business?

- What is the role of CLV, and how will it be used?

What kind of data is available?

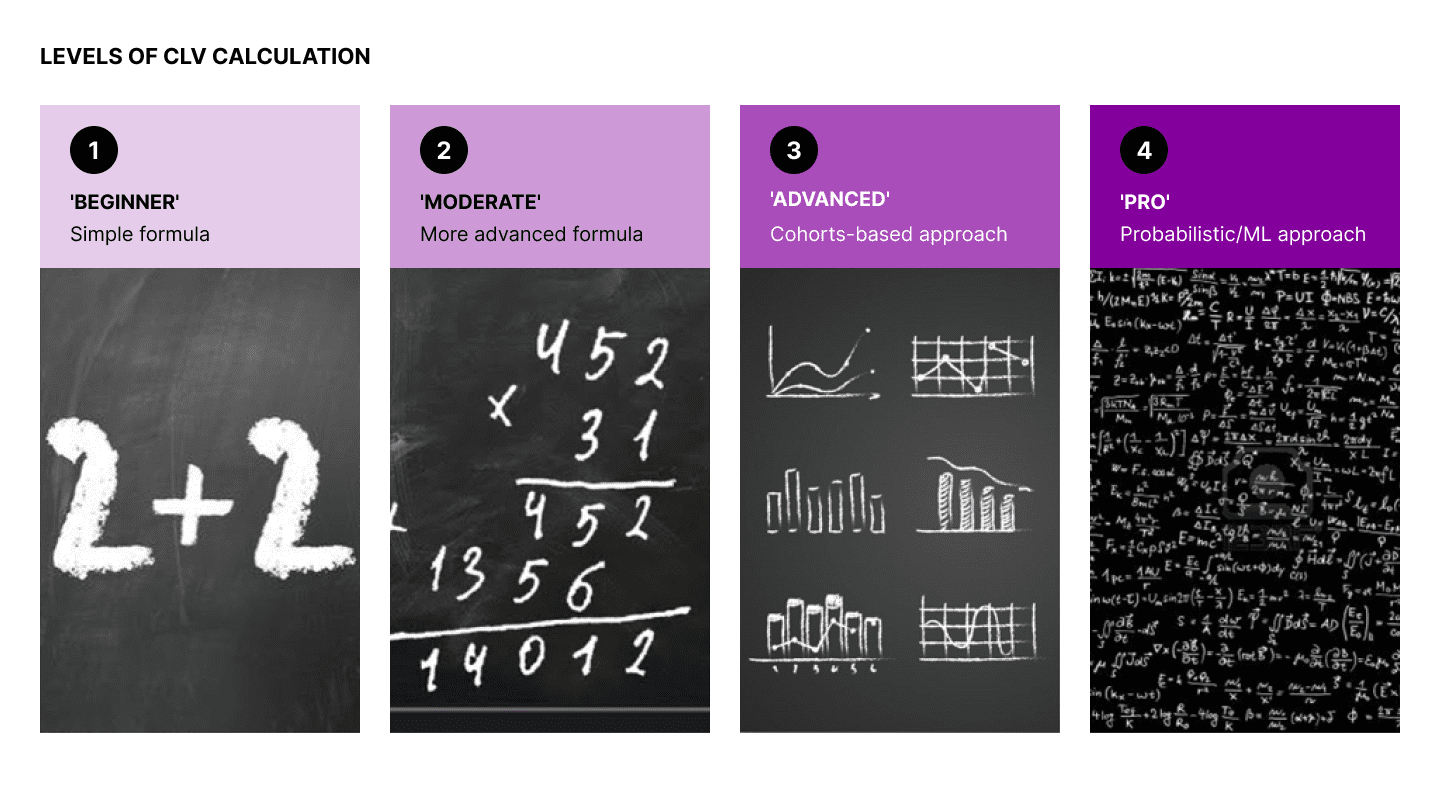

In our experience, we have seen 4 different levels of CLV maturity

- Beginner – usually CLV is calculated as a very simple formula by taking the average of customer spend and multiplying by the tenure we expect the average customer to have. The method extremely simple and intuitive, but appropriate only for very early stages — as it does not provide any distinction between different customer base segments.

- Moderate approach – still based on a rather simple formula allowing to calculate and compare CLV for distinct user segments. The drawback of this model is that the absolute CLV number might not be accurate, as customers tend to have a fluctuating churn rate over time. This is extremely important for new customers as first months have rather high churn rate and then, over time, it stabilizes.

- Advanced (cohorts based) approach – allows to have accurate CLV evaluation for various segments, however, requires a rather high amount of historical data and big segments sizes. The main idea behind the cohorts approach is that a cohort should be observed for a long enough period of time, allowing to calculate long term churn.

- Probabilistic/Machine learning approach – based on complex calculations allowing to calculate CLV not only for customer segments, but also for individuals. These methods are the most advanced ones at the moment, and require a low amount of historical data. However, they are rather complex to implement for the first time

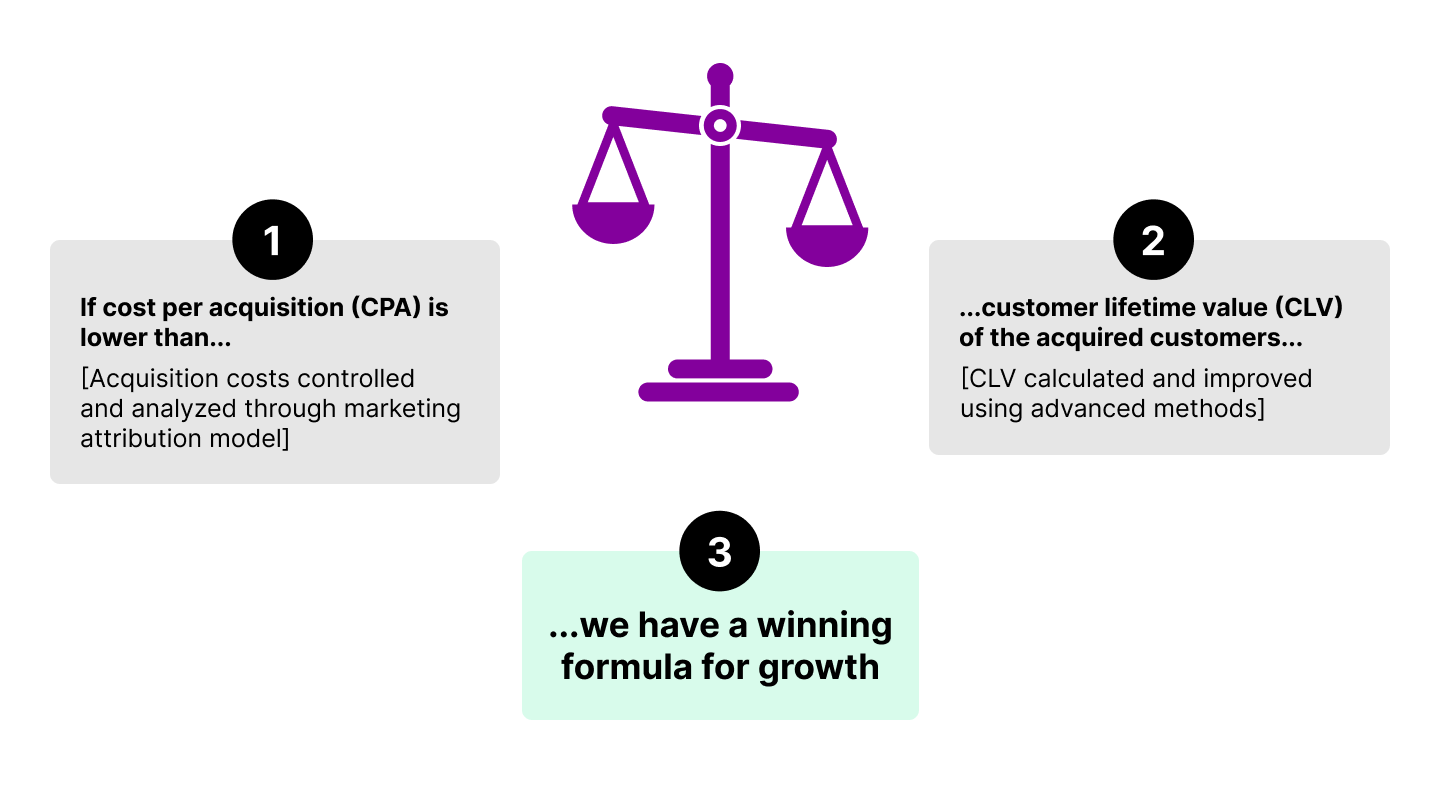

Customer acquisition optimization

One of the main advantages of knowing CLV is to compare it to customer cost per acquisition (CPA). Only if CLV is higher than acquisitions costs, it is possible to have sustainable growth and the business has potential to be profitable.

This is not a new event for small companies, and most businesses tend to have an idea about how much, on average, is their customer worth — given some specific period as well as evaluate blended acquisition costs (CPA). However, the problem arises when business is growing and starts using more acquisition channels which are priced differently, and different acquisition channels are bringing customers with different value.

Consequently, this raises the need to understand CLV and CPA at the lowest level possible (e.g. marketing channels, customer segment, etc.). That is when marketing attribution and more advanced CLV calculation methods come into play.

Customer value management

One other traditional CLV use case is to use it as an input to customer value management. In this case, companies would have a goal of improving CLV by using various actions with users. Such actions could be: price changes, discounts, services improvement or any other campaign.

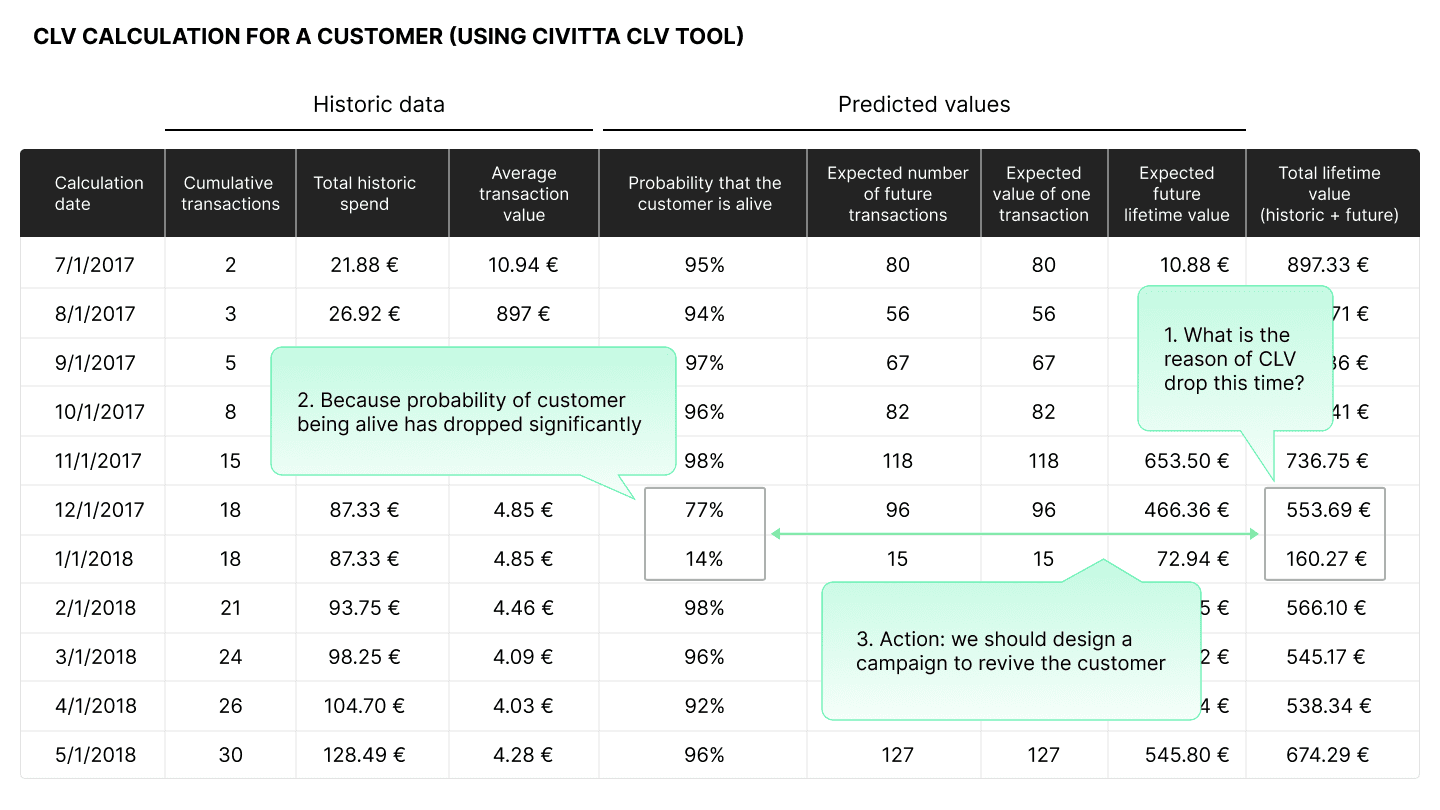

In the example below, we are presenting how a raw output of advanced algorithms might look like. Each row represents one calculation in time of both historical and predicted values relevant to CLV. As it is calculated per each individual, it allows to constantly track each customer behaviour and react to any unexpected changes.

In the example above, calculations are ran monthly. The calculation, which was completed on 1/1/2018 using the available historical data at the time, shows that this customer has decreased in probability of being “alive”, resulting in expected total lifetime value decrease. Given this information, it would be beneficial to include this customer into the campaign which is designed to revive customers who have high chances of churning.

Summary

To sum up, the most important CLV exercise is to apply your customer data in a pragmatic way in order to understand the most critical threats to customer transactions (i.e. revenue contribution). The key is to identify which business problem (or problems) you want to solve using CLV, evaluate your maturity and choose the most appropriate CLV calculation method.

As an example, if you want to understand which of two customer segments is more valuable, the second approach based on a rather simple formula is enough. However, if your goal is to dynamically generate and send an email or notification to customers who have high likelihood of churning, then probabilistic methods should be used.

Read the full paper here.