Possibilities and risks of carbon offsetting

Introduction

The effects of climate change are already felt everywhere, and we need to start dealing with it immediately. Both public and private sector organisations have an ambitious task to reduce the climate impact caused by their activities significantly. To a large extent, the commitment comes from the EU’s Green Deal, within which Europe must be climate-neutral by 2050. But what can be done to contribute to a more sustainable future?

One of the main ways is to start reducing your climate impact. There are several methods to reduce the climate impact directly, but they can be time-consuming and expensive, so many organisations are turning to compensation efforts. The idea of offsetting is that a project is carried out on behalf of an organisation, company, or person for a certain fee during which emissions are removed or reduced. Carbon offsetting is a very appealing way for companies to do a lot without much effort. And it tends to be so when something sounds too good to be true.

Carbon offsetting has come under criticism from scientists, sustainability experts and other interest groups, often rightfully so. It is considered one of the primary means of greenwashing. Namely, the danger is that compensation is used to continue polluting activities without reducing one’s impact directly. To achieve changes and not fall victim to greenwashing, companies should primarily mitigate the climate impact of their activities by using alternative measures. If, and only if, a business has reduced emissions from its operations to a degree that any further direct emissions reductions are impossible, carbon offsetting can be considered. This article outlines some criteria to remember to make the right and educated choice.

What is carbon offsetting?

Carbon offsetting can be defined as the reduction or removal of greenhouse gas emissions to offset the emissions of a company, organisation or individual.

- Reduction or mitigation includes activities that prevent emissions, such as investing in renewable energy or nature conservation.

- Removal projects involve sequestering carbon from the atmosphere. Planting trees is an example of a removal activity because trees sequester carbon. By using newer technological means such as Direct Air Capture (DAC) and Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), reducing the amount of carbon in the atmosphere is possible.

The logic of compensation is that if it is impossible to reduce or prevent one’s greenhouse gas emissions, then its climate impact can be balanced through someone else’s actions elsewhere. One example is flight compensation. Since it is difficult to reduce aeroplane emissions directly, the climate impact of flying can be balanced using compensatory measures. By measuring how much CO2eq is generated during one flight, it is possible to calculate how much CO2 the compensation project corresponding to the flight should remove from the atmosphere.

Compensation projects are verified, and various compensation programmes sell related credits. The programmes are responsible for determining the projects’ validity and their fulfilment of quality criteria. Since the quality criteria are not uniformly regulated, the programmes can largely decide how they evaluate the projects. Some of the more well-known programmes are, for example, the Gold Standard, the Clean Development Mechanism (a UN compensation programme) and Myclimate.

What should a high-quality carbon offset project look like?

Although there are different metrics to evaluate compensation projects, experts generally focus on five quality criteria.

The criteria require the project’s activities to be additional, correctly assessed (not overestimated), permanent, exclusive, and unrelated to other environmental or social harms.

Additionality

A project is considered additional if its activities are not carried out without the compensation market. That means that the project activity is not additional if:

- the project activity is required by law or is already customary in an industry,

- the project is economically viable without income from the compensation market.

For example, in many countries, the construction of renewable energy plants is already required by law or is customary, so it would not meet the additionality criterion. Additionality is one of the most important criteria offset projects must adhere to. Otherwise, all compensation would lose its meaning.

Correct assessment of emissions

The biggest danger in estimating the correct level of emissions is overestimation. If the baseline level of the project’s emissions is too high, then the assessment of the project’s contribution to climate impact reduction is mistaken, i.e., the project’s impact is overestimated.

Although the risk of overestimation is more common, reduction projects can also underestimate actual emissions reductions. The result is the same – the project’s contribution is smaller than initially calculated. It is more economically beneficial for compensation project vendors to rely on more optimistic assumptions that may not hold true later.

There are several examples of projects where the assessment of the emissions level has been incorrect, and larger programmes have also been guilty of it. For example, methane capture projects from the Clean Development Mechanism have been found to realise only 35% of their intended emissions reductions (read more here).

Permanence

Along with additionality, permanence is also one of the key pillars in evaluating high-quality compensation projects. The carbon sequestered or emissions reduced due to the project should be permanent because offset emissions are also permanent in the atmosphere. Since CO2 remains in the atmosphere for centuries to thousands of years, offset projects should also ensure the same removal/reduction duration.

For example, if a company calculates the total emissions in CO2 equivalents, it expresses the impact in a 100-year perspective. So, the offset would also have to bind carbon for at least 100 years for the math to work out.

Meeting the permanence criterion is most difficult for biomass projects (e.g., planting or protecting forests, agriculture, etc.) because they have the highest risk of reversal. Reversal here means the occurrence of unintended emissions during the operation of the compensation project. For example, a project will plant trees that sequester carbon. In the event of a forest fire, the sequestered carbon is released back into the atmosphere, and the compensation is invalid.

Meeting the sustainability criterion can also be jeopardised by non-natural factors. For example, if a practice that increases soil carbon sequestration ceases or wood is not used to produce long-lasting products but instead is burned. Various defence mechanisms are used to avoid such scenarios. One of them is buffer zones, but they require additional land, which results in higher project prices. According to critics, buffer zones are only helpful for natural reversal events.

Exclusivity

In order to ensure exclusivity, it must be established that the carbon credit being sold has a unique ID number, which is removed from the market once purchased. There is a risk of double counting the same carbon credit when several parties use the same credit.

The risk of not ensuring exclusivity is unlikely in the case of better-known compensation programmes, but due to the market’s growth, it is worth being careful.

Not associated with environmental or social harms

Although the compensation market focuses on climate impact, other environmental and social factors, such as water quality, species richness, living conditions of local residents, jobs, etc., must also be considered.

It is this criterion that can be decisive when selecting a compensation project. Therefore, many projects have begun to offer, in addition to reducing the climate impact, other environmental and social benefits, which may include, for example:

- offering job opportunities

- improving air or water quality

- improving species richness

- improving access to healthcare

What are the risks?

The carbon offset market can be a treacherous place. Therefore, consumers must be diligent and critical. Some of the aspects that make carbon offsets such an unreliable tool are that there is a lot of subjectivity in evaluating quality criteria, and most of the projects cannot adhere to all five quality criteria. That holds true for several verified projects due to the lack of a consistent and uniform methodology for evaluating projects.

Owing to the risks associated with the compensation market, several companies and organisations have announced that they do not use carbon offsets to reduce their impact but do so through direct action. For example, the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi), which exemplary companies can join to verify their climate pledges, allows the use of offset projects only after the company’s emissions have been reduced by 90-95%. The companies that have joined SBTi include, for example, the energy company Orsted, the packaging company Tetra Pak, commercial goods seller Orkla, and many others.

The compensation market is complex and requires savvy consumers to navigate. It is important to focus on specific projects and programmes when making decisions and critically assess their compliance with the quality criteria examined here. Making the wrong decision can have terrible consequences by being accused of greenwashing. For example, in May 2022, the Dutch airline KLM was sued for greenwashing (read more here).

A seemingly simple solution might not be the best

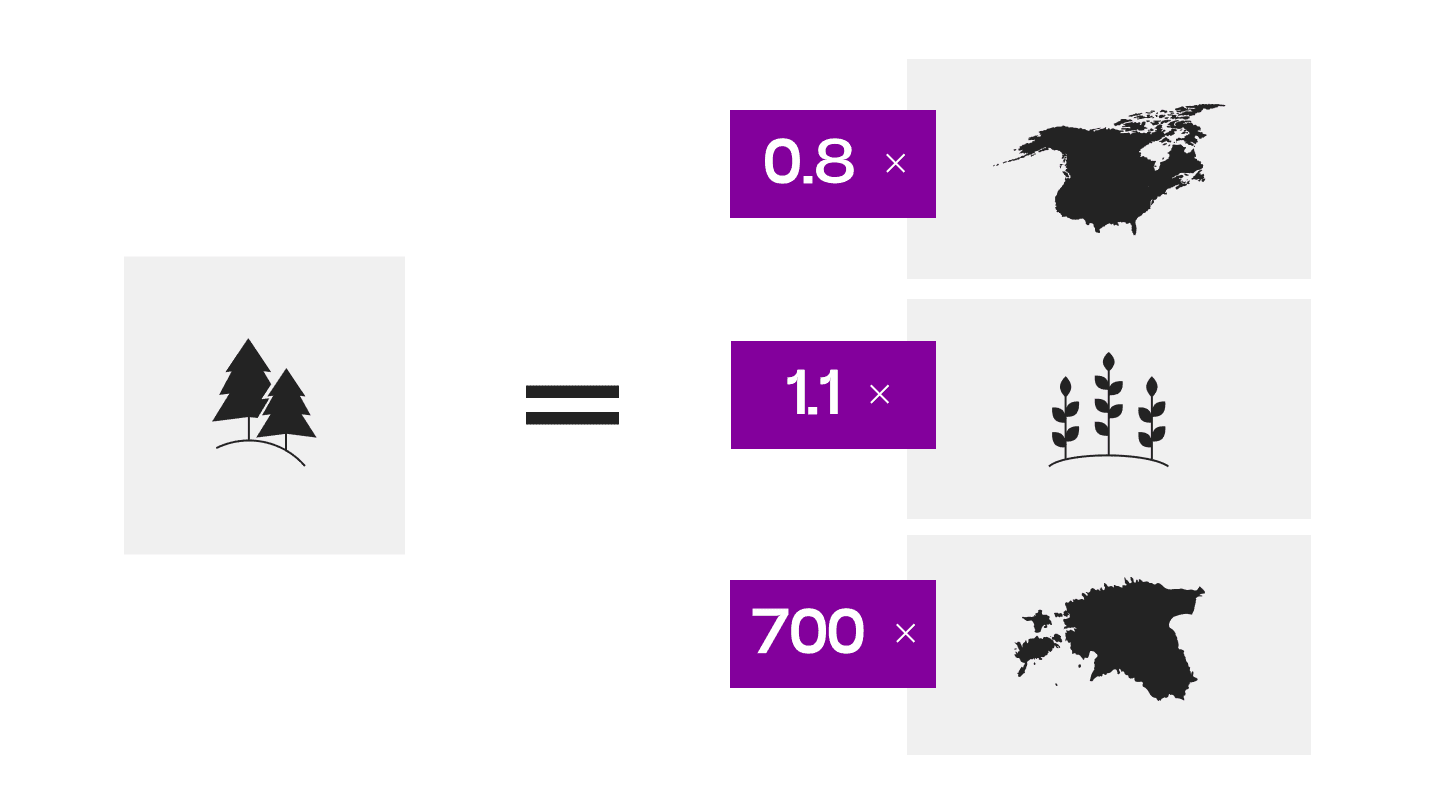

Although risky, tree planting projects are among the most common projects different programmes offer. To compensate for all of the world’s emissions that occur during one year by planting trees, we would need approximately 1.6 billion ha of land.

For reference, this is 700 times more land than the current area of Estonian forests, and a similar area is covered by the world’s current agricultural lands (1.5 billion ha) and the entire area of the United States and Canada combined (1.9 billion ha).

From the limited land resources alone, it is clear that planting trees will not solve the problem.

What does the future hold for the carbon offset market?

At the moment, offsetting has been used as a simple, cheap, and fast way to reduce the climate impact of a company, organisation, or person without having to make major changes in their activities. Inexpensive but low-quality offset projects are widely available on the market. Still, more expensive and higher-quality projects are also emerging, with demand greater than current supply (direct air capture, for example).

Public criticism of the low-quality compensation projects currently on offer has increased from both organisations in the public and private sectors. It is clear that low-quality offsets do little to reduce climate impacts. Both sellers and consumers of carbon offsets will likely have to adjust to more regulations in the coming years, leading to the exclusion of low-quality projects. From the company’s point of view, this means that the risk of being accused of greenwashing is drastically increased if low-quality compensation credits are used.

Likely, most projects coming to the market in the future will be carbon removal projects instead of reductions. One of the most promising technologies, direct air capture, is also gaining more and more popularity. Long-term storage or binding into long-term carbon products must accompany direct air capture. Today, this typically means burying CO2 100-1000 meters underground. However, not all geographic locations are suitable for storage, so finding suitable locations is the main issue.

The European Union wants to specify and harmonise the quality criteria of the voluntary carbon market, which may mean that some of the solutions on offer today might need to meet the new conditions. For compensation credit buyers, this can manifest as bad PR because it may appear that the offset used is of low quality. The compensation market is developing rapidly, but only the following years will reveal its direction.

We at Civitta are happy to help you navigate the jungle of the carbon offsetting market. Feel free to get in touch.